AS TOLD TO

Gemma Latham

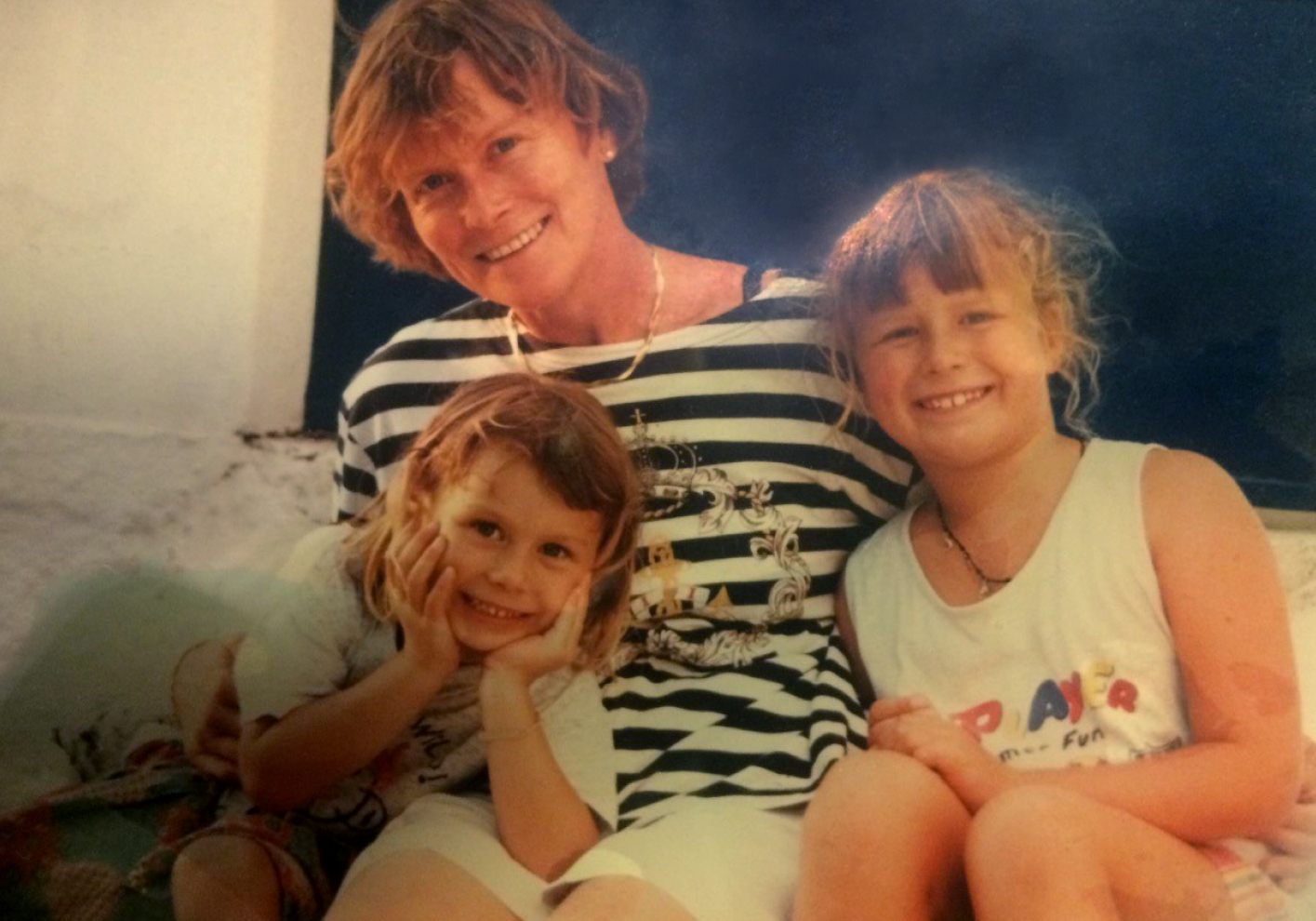

For someone who works in financial services in the City, I’d say my background is relatively unconventional. I grew up on a Greek island called Naxos in the Cyclades and I’m bicultural – my mother is English and my father was Greek. My sister and I were brought up by my mum in a low income and largely single parent household. At home everything was in English, but I went to a Greek state school and my friends were Greek or ‘half and halfs’ like me.

My father suffered from a chronic illness, which led to him becoming disabled and living on a different island for most of my childhood. Prior to that he was not very present; my parents had an unusual but mostly good relationship. They separated when I was young, but remained friends, with my mum caring for him financially and otherwise until he passed away a year ago.

Financially, things were difficult. My mum, who is a remarkably kind and inspirational woman, had to work multiple jobs to ensure my sister and I would have options. These circumstances eventually took their toll on me and as a teenager I developed quite severe anorexia and depression. My relationship with my dad changed a lot over the years and eventually we became a lot closer; we were also fortunate to have close family on my mum’s side looking out for us, but having to learn to live in what are quite unusual and challenging circumstances at a young age definitely shaped me as a person.

Looking back on it now, I would say that coming through that, the eating disorder in particular, and recovering, gave me a very different perspective on life. I sort of matured overnight and it made me very excited for the opportunities that are out there. I was anxious to leave the island I grew up on, to discover where my potential could take me and also get away from the stigma that was attached to being the girl who’d had anorexia in a small and often judgmental society. I think when you hit rock bottom and you manage to come out the other side, there’s a period of time where you feel that the world’s your oyster.

My experiences instilled in me an interest around people’s mental health and the interconnectedness between that, your ambitions and the things you’re interested in. With the benefit of retrospect, I also think it’s made me more perceptive and sensitive to the things that people have going on behind the facade that you see. We all have things that happen to us, and how you manage that on an ongoing basis can have a really significant impact on the outcome. That’s one of the reasons why I became very passionate about mental health and wellbeing in the workplace.

My particular focus at Barclays Ventures has been on ESG-aligned strategies and investments. I’ve led on wellbeing – financial and non-financial, healthy ageing being a particular area of interest within that, sustainability and the transition to a net zero economy. Recently I’ve been focusing more specifically on the future business model of consumer banking – FinTech and what that means – as well as looking at how consumers are interacting with cities, in context of behaviour change and the transition to a net zero future.

It took me a long time to realise it, but the life experiences that I’ve had – where I grew up, my academic background and the things I’ve done outside of my day job – have actually been really important in giving me the skills I’ve needed in my career. Growing up in between two cultures there was an element of feeling like I never really fit in, but from a very early age I constantly had different perspectives, different languages, different ways of doing things. And that instilled in me a curiosity about people – what it is that drives us, what makes us different, what makes us the same – as well as a love of travel and of languages.

There are advantages and disadvantages to the upbringing and experiences I’ve had, and I’ve reflected on this a lot. My family situation taught me resilience and tenacity. I’ve had to work really hard for things, and I think that’s a good thing. I’ve had a job since I was 14. I worked in the hospitality industry and, actually, what I learned in those roles has really helped me when it comes to people skills, communicating and dealing with different types of people.

Today, I see the advantages of all these experiences – how they are a part of my skillset, perspective, drive and how they prepared me for the challenges I face working in a competitive industry – but I did not feel comfortable talking about my own journey up until recently. I used to feel (and sometimes still do) a certain insecurity and that it was a hindrance and a big disadvantage that I had.

When I first left Greece and moved to the UK to go to university, I very much went from being a big fish in a little pond to being a tiny fish in a very big pond. I experienced a lot of the imposter syndrome of coming from a small place, not having been to a very good (or private) school, not having travelled, not having done a lot of the things that my peers had seemingly done. And – even more relevant, I think – not having that confidence that I saw a lot of people having.

For a very long time, all through my university and first years in a bank, I suffered from this imposter syndrome and a constant feeling of not being good enough to be there. In the industry that I’m in, the first steps that you take in your career are considered very important. More so than I realised at the time. There’s often an assumption that your choices have always been intentional, guided by your real passion or your real interest, and people can make snap decisions about you. That is a disadvantage. I’m hoping it will change, but it’s very much ingrained in how people think about talent, or people.

In reality, if you’ve come from a disadvantaged background and not had the benefit of parents with expertise and careers advice, school counsellors, or career services that can give you guidance, you don’t know that these things will matter down the line and in more ways I think you have to discover your path through trial and error. If you are a young adult with no-one to ask for advice, you have to figure out what you want to do and what makes the most sense by yourself. And perhaps you just need to get a job because you need to provide financially. But the expectation is often that we’re all being intentional and seeking out the best opportunities from the get-go.

Even today I’m always asked about my background, the choices I’ve made and why I made them. There have often been times where I’ve been questioned about a choice I made when I was 18 or 20 years old, and the honest answer is that I didn’t know what I didn’t know, so I just had to try things and see if they worked for me.

Sometimes I get a positive response from being honest – I see that people really respect and value it. And others don’t. I am mature enough and comfortable enough in my own skin now that I can say ‘well, actually maybe that wasn’t the right opportunity for me’ but in reality it can still be difficult to deal with rejection and avoid feeling inadequate.

Now, I realise that my background and experiences are very much at the heart of who I am, and the value of an individual’s life story and experience outside of the workplace, which is why I think it’s so important to champion open conversations about these issues and bring them into my work.

I do think there is a growing recognition by employers that people’s experiences outside of what you see on their CV – and their demonstration of their skillset and mindset – is increasingly important. In the era that we’re living through there’s so much change when it comes to technology, climate change, what our jobs are going to look like in a few years’ time. And that’s not even mentioning Covid. There are so many trends that are going to completely change the sort of landscape that we’re in.

And so, when I think about the skills of the future, in this constantly changing environment, they are things like resilience, an entrepreneurial spirit, ability to adapt and learn, flexibility, intellectual curiosity and cross-industry collaboration. And actually, a lot of these are things that can’t really be taught. The experiences that you have, and that you’ve sought to have, in a non-professional context are therefore becoming increasingly important, which is why we should be focusing more on diversity and inclusion from a socioeconomic perspective as well.

The cultural aspects of an organisation and a business are really important. Being in the right environment and having the right sort of role models and management around you can make a huge difference to what an individual can accomplish. People who look different or who have a different background have often dealt with very different types of circumstances and situations in their life, so as leaders you would hope that they’re able to develop a more representative and helpful culture for their employees overall.

Communication in the workplace is also really important, particularly at the moment with a lot of people still working from home and being remote. At a time when people may well need more emotional support than usual, the informal conversations that would usually happen are harder to have, making it difficult to maintain that sort of dialogue and openness. It’s also become a lot harder to separate your personal life from your professional life, particularly for people with children.

Creating a psychologically secure environment for people to feel comfortable talking about the challenges that they’re facing and what they’re going through is essential. Authentic leadership and having open communication channels – particularly as a manager or someone in a position of influence – is the best way that I’ve found to encourage good mental health in the workplace. Being quite open, and perhaps a bit more forthcoming than you would typically be, about your own experience and the challenges that you yourself are facing can help to make others feel comfortable talking about their own situations. If people feel like they’re in an environment where there’s trust, and that they’re not going to be penalised for discussing a difficult situation, I think that can be very powerful and positive and ultimately lead to increased productivity.

Drawing on my personal journey, I lost my father during the first lockdown, which had a significant impact on my mental health. Being in a supportive environment made a very big difference, as did learning to be more forgiving with myself; something that doesn’t come naturally to many ‘insecure, overachieving’ City folk.

This is also where diversity and inclusion is really important within a workforce and especially at board levels. Generally speaking it is widely accepted that women are empathetic leaders, and it is a characteristic that can be extremely helpful in a time of crisis, both personal and systemic. It also ties in with my thoughts on the value to be found in people’s own life experiences, because I think people who have had to overcome adverse circumstances, have had to develop resilience to come through that and are potentially going to be better placed to be authentically empathetic.

Of course, in a professional environment there’s a job that still has to get done. People have to work hard and there are deadlines to meet, so it’s important to be empathetic in a way that actually helps people to get through things. There is a difference between empathy and sympathy. I think empathy is really important, sympathy less so in a professional context. It’s a difficult balance to get right, and this is why we talk about culture. Culture in a professional sense is a really difficult thing to put your finger on, but I definitely think it’s linked to diversity, inclusion, communication and the policies that you have in place, and all of these are very interconnected.

Margarita Skarkou is a founder member of Barclays UK Ventures, an initiative set up in 2018 to build new technology-led businesses inside and outside of traditional banking through organic-build, partnerships and venture investments. She is on the advisory boards for the Next Generation NED Network, the Global Thinkers Forum development committee, Barclays Women on Boards network, and Women in Finance. She has been recognised as a Woman Future Leader by McKinsey and Young Leader by the president of the Hellenic Republic for her work as head of strategy at the Greek Economic Forum. She was also named one of Brummell’s Inspirational Women in 2019 and 2020.