WORDS

Nick Smith

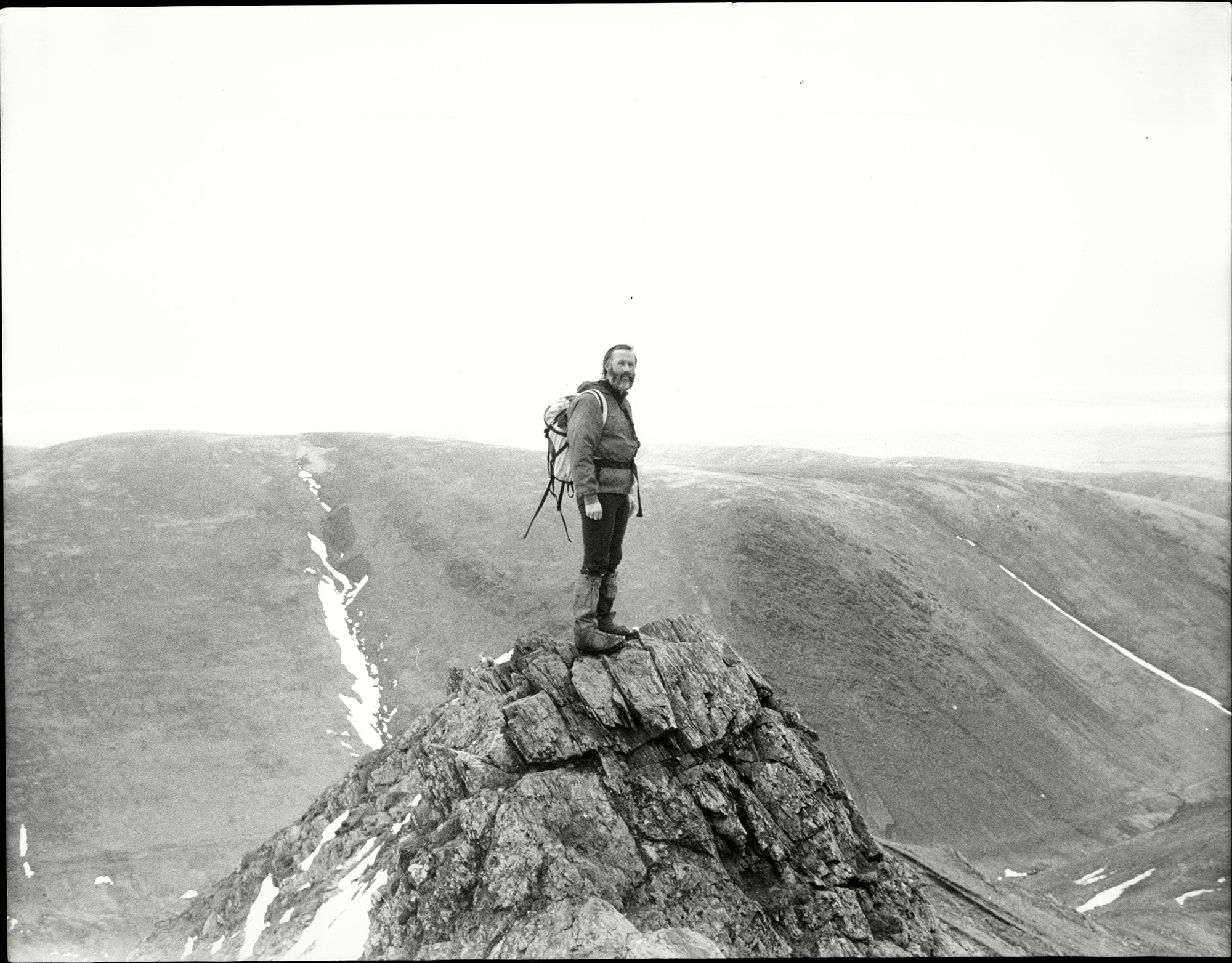

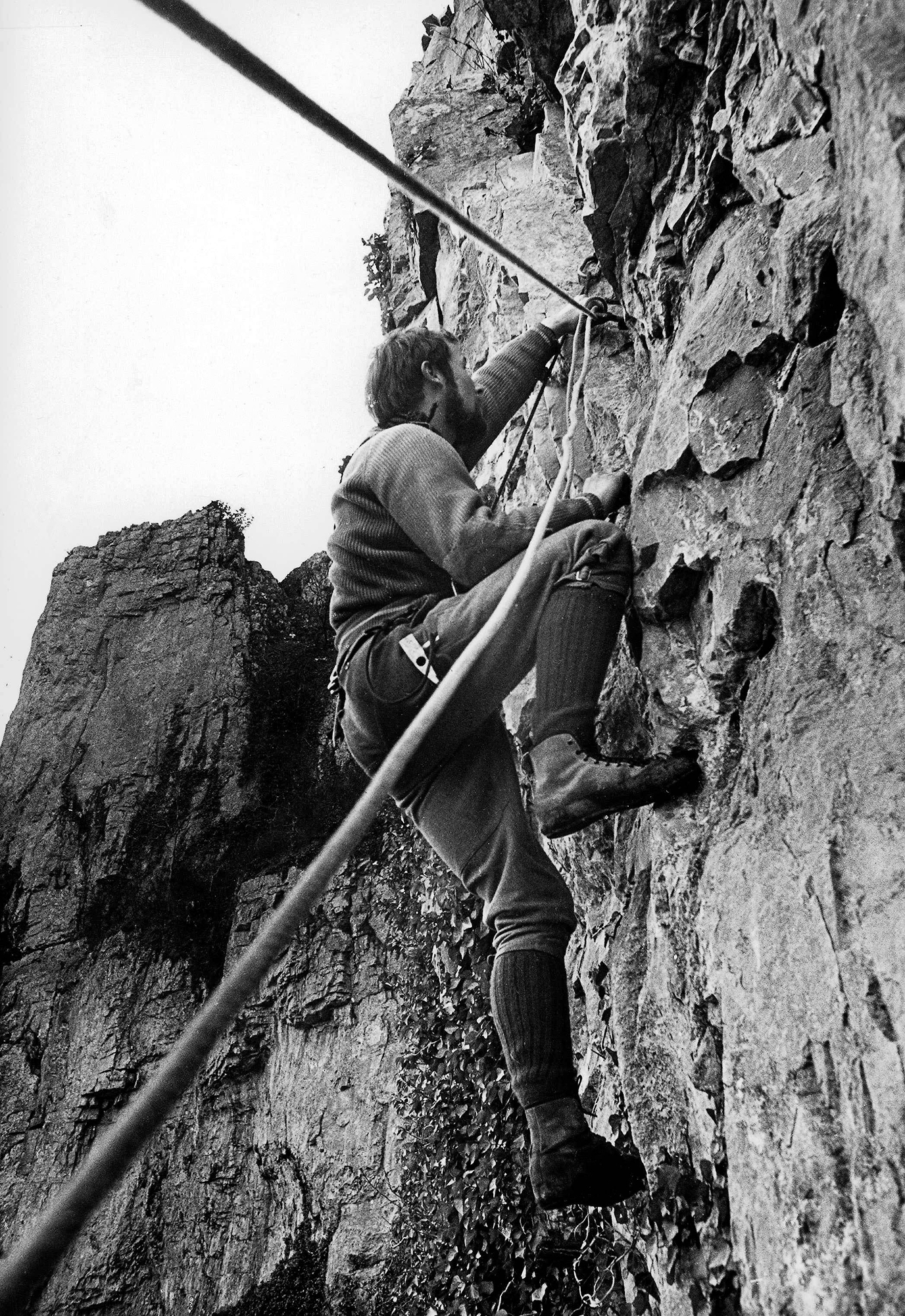

When asked why he still does it, he replies simply, ‘Because I love it.’ Sir Chris Bonington, mountaineer of rare distinction, despite being in his eighties, still makes light of adventures that would challenge anyone half his age. A few years ago he celebrated his 80th birthday by summiting the Old Man of Hoy with today’s rising star of the climbing world, Leo Houlding. It was a bittersweet moment for Bonington, who back in 1966 became the first to scale the technically daunting Scottish sea stack. He did it, ‘as some sort of catharsis’ to come to terms with the death of his first wife Wendy. ‘It did help,’ he says. But what left its mark on Bonington was that almost half a century after his original ascent, he was still able to make the climb. ‘OK, I didn’t lead, and I was in great pain, as I’d slipped a couple of discs in the process. But I did it.’

Bonington became a household name in 1975 as expedition leader of the first successful ascent on Mount Everest via the murderous southwest face, a feat immortalised in his gripping bestseller Everest the Hard Way. As expedition leader, he wasn’t to set foot on the ‘roof of the world’ on this occasion, ‘because there was too much to do organising the logistics.’ Bonington, who had a brief military career in the Royal Tank Regiment in the 1950s, says that there are interesting parallels between military planning and climbing. ‘Campaigns are won by the flair and genius of the commander combined with good logistics. Climbing is a lot like that.’

A decade later, he was to reach the summit. It was an achievement that gave him the record, however briefly, for being the oldest person to do so. ‘I was 50 at the time and was just repeating a route that had been done before. I think I was only something like the 260th person to get to the top. But it was a great adventure.’

Despite the dozens of first ascents and Himalayan expeditions under his belt – which he describes in his new memoir Ascent: A Life Spent Climbing on the Edge – it’s perhaps ironic that his most famous exploit was a breathtaking retreat from the fearsome ‘Ogre’ in Pakistan’s Karakoram Range in 1977. In an improvised descent, during which he broke several ribs, Bonington guided his comrade Doug Scott home to safety. Scott had broken both legs in an abseiling mishap after summiting, and was forced to crawl down the mountain. ‘I tried to be cheerful, telling Doug that he was a long way from dead. But we went five days without anything to eat. Fortunately, we had enough gas cylinders so that we could melt snow. Five days without anything to drink would probably have been fatal. I had to down-climb after him, coiling the ropes as I went, with visibility almost zero and no one to catch me if I fell. I knew that if we didn’t get back quickly we’d be dead. But you focus on staying alive.’

We’re living in the present and moving into the future. That’s always been my philosophy

While he says he is ‘incredibly glad’ to have had his Himalayan experiences when he did – ‘because we had the place to ourselves’ – unlike other senior climbers he’s got no problem with the soaring popularity of guided and commercial climbing on Everest. ‘These days you can have a thousand people at Base Camp and a hundred on the South Col, where there are fixed ropes all the way to the summit. But I don’t begrudge that in any way.’ He says it’s no different to tourists being guided up the great Alpine peaks such as Mont Blanc or the Matterhorn a century ago. ‘For each of those people going to the top on fixed ropes it is still the experience of a lifetime. Climbing is adventure, and adventure is alive and well today.’

Behind the peaks of success, there lurks a shadow of tragedy over his career, something that still brings a note of sadness to his voice. The deaths of many mountaineering friends weigh heavily on his shoulders. There was Ian Clough on Annapurna in 1970, Mick Burke on Everest in 1975, Nick Estcourt on K2 in 1978, Pete Boardman and Joe Tasker on Everest in 1982. These bereavements would be enough to bow a lesser man, and yet Bonington – who is a great believer in ‘living for the moment’ – emerged more determined than ever to roam the world’s ranges in a career that was later to take him away from his beloved Himalayas as far afield as Greenland and Antarctica in search of unclimbed peaks. ‘You can still find hundreds of mountains that no-one’s climbed before, especially in India and Nepal. They’re not unclimbed because they’re too difficult, it’s because no one can be bothered, because you won’t get famous for climbing them. But you will get all the joy of being on a mountain on your own. That’s what I’ve been doing these past few years, essentially going into regions that the big trekking companies haven’t discovered yet.’

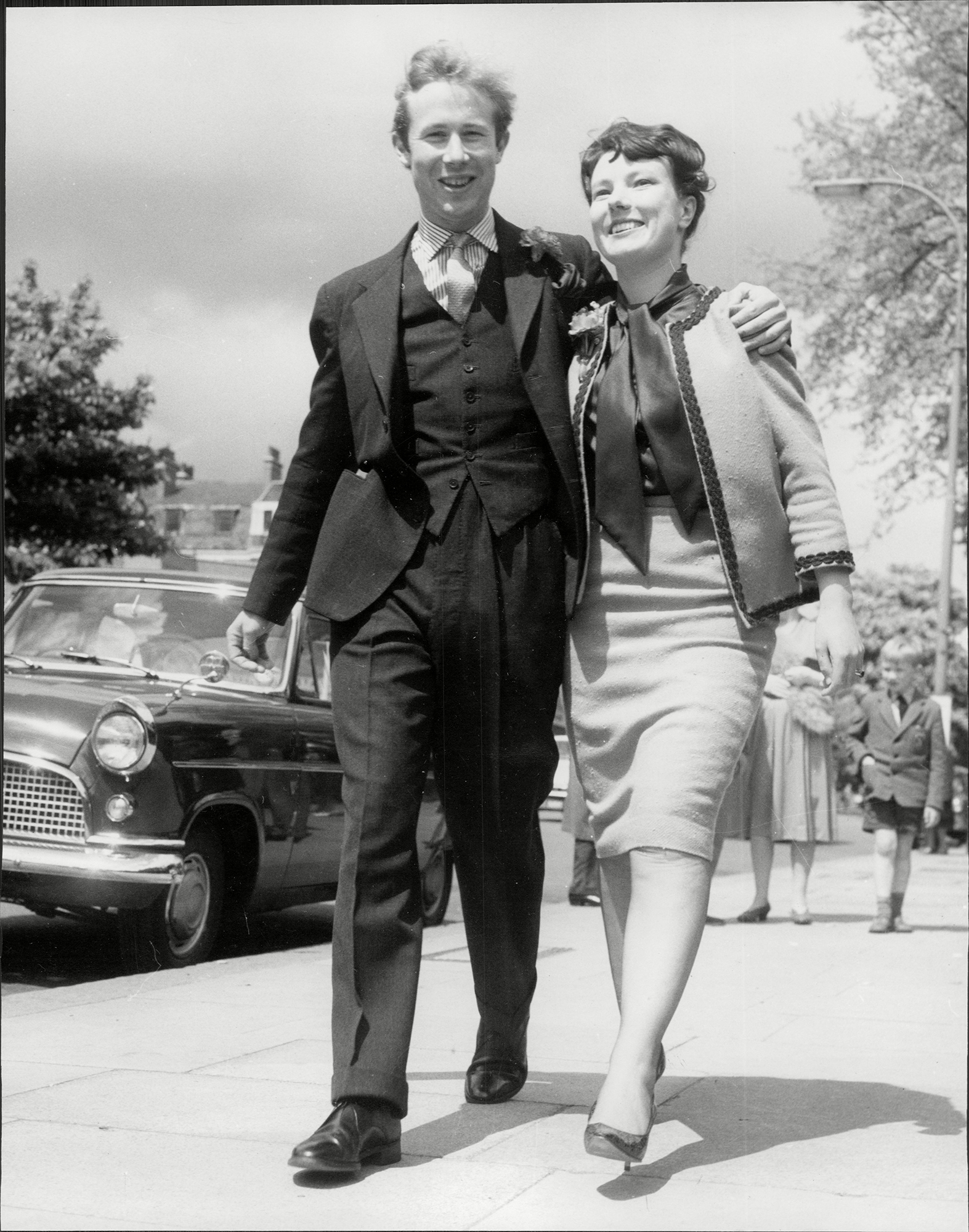

Chris Bonington And Wife Wendy Marchant.

Bonington says that he found writing his memoirs much harder than climbing. ‘It was very, very tough, particularly as it goes into my personal life. But it was something I needed to do.’ He talks about how, in trying to reach perspective on his ‘unusual childhood’, he researched his mother’s diaries, and re-lived his impoverished years, the son of a single mother. He talks of the death of his first wife Wendy, lost to motor neurone disease in 2014, the death of Conrad, their first child, and, of course, the loss of so many of his climbing colleagues in the Himalayas. ‘You learn from experience,’ he says. ‘But you never allow yourself to wallow in it. That’s how Wendy and I got over the loss of our child. We looked to the future and quickly found ourselves with two more sons to enjoy.’ Bonington describes Wendy’s death as a ‘huge grief ’ and his outlook at the time as ‘pretty miserable’. But he goes on to describe the joy of starting a new chapter in his life on meeting his new wife Loreto, who he married in 2016. ‘I think we’ve found something new and different in the autumn of our lives. We’re living in the present and moving into the future. That’s always been my philosophy.’

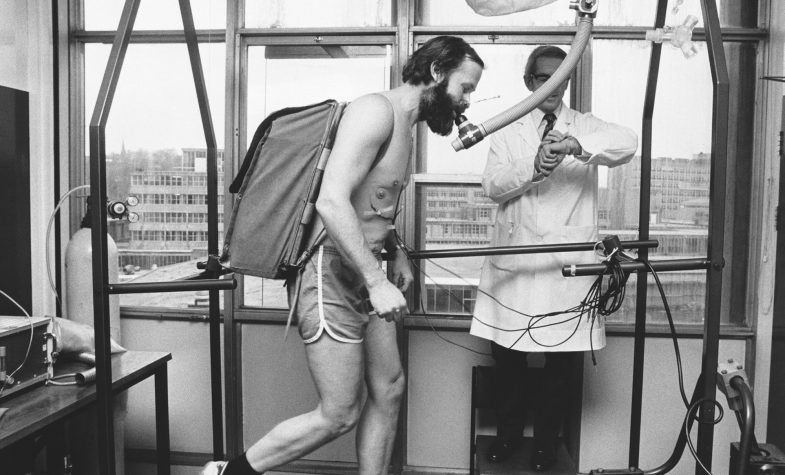

Even the great Chris Bonington has been forced to admit that these days he’s not quite the supreme athlete he was back in the 1970s. But he still regularly hikes and climbs, while his commitment to British mountaineering is as strong as ever. But now it’s time to take things more easily as he prepares to go on a cruise to see the Northern Lights with Loreto. ‘The great thing about a cruise,’ says the legend of the Himalayas, ‘is that all you can do is sit back and enjoy yourself.’

Ascent: A Life Spent Climbing on the Edge by Chris Bonington; £20, Simon & Schuster