Brummell catches up with renowned Italian winemaker Maurizio Zanella of Ca’ del Bosco

The appellation of Franciacorta, Italy’s highest-regarded sparkling wine, was established in no small part by a man who was there as a punishment. Here, he shares his stories of building reputation and taking risks.

How did you come to the area of Franciacorta in the first place? You weren’t born here, were you?

I was born in 1956, in Bolzano in South Tyrol, in the mountains. We moved to Milano when I was very young, but my mother wanted a place where she could keep chickens, grow apples… and so she bought this small farm [he points to the walls of a dilapidated cottage among the vines]. And then, at the beginning of the 1970s, I was a bit of a naughty boy, so I was sent here to get me out of Milan.

That period was very volatile in Italy, wasn’t it? Gli anni di piombo (“the years of lead”), with extremist politics getting violent. Were you involved in that as a teenager?

It was after the 1968 student revolutions in Paris and in Italy. I was only 14 but next door to my school was a university that had been taken over by Lotta Continua, who were beyond communist, they were so far left. I was at a private school, full of fascists, and I had to be different. And I was drawn to these people who were fighting with the police. It was very exciting, so I spent all the time I was supposed to be at school with the party at the university.

So your parents sent you to the countryside?

At first they just moved me to a state school to retake the year. But that school was full of communists, so I lost another year hanging around with fascists. Next, my father, who owned a transport company, sent me to Liverpool to work at the docks. Maybe they wanted to turn me left-wing again, but I could hardly understand a word they said! Finally, my parents decided to send me to live on the farm and go to school in Iseo.

You say farm – was it a vineyard, too?

Well, the farmer did make some wine, but it was closer to vinegar, and we only had two lines of vines. Honestly, the quality of Italian wine in general was very low at that time – people were incentivised to produce as much as possible, as cheaply as possible. But one day someone from the Lombardy agricultural department came and said they were organising a trip to Burgundy, Champagne and Paris. I had no interest in wine, but I was a 16-year-old guy… I heard Paris and thought, ‘Moulin Rouge!’ So I begged my mother for permission to go.

So, was that the “road to Damascus” moment for you? Or the road to Taittinger; your conversion to the joy of winemaking?

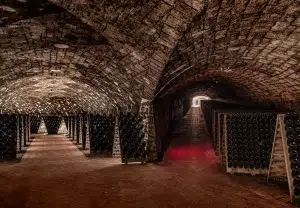

In a way. The bus left in the middle of the night, and we arrived at this domaine in Burgundy in the morning. Everyone else in the group were these old noble landowners, who only grew vines for the subsidies they received. But I knew nothing, so I just listened. And we went round the vineyards and cellars, and they were just criticising it all… old ladies grafting rootstock instead of just buying new vines; the vineyards being too tightly planted for automation; the mould on the wall… and the price of the wine. This was Romanée-Conti!

So, if you were hearing their negativity, how did you fall for wine?

At the next harvest, my parents were at the farm, and I had to show my father that I was smart, that I knew better. So, I started telling the farmer he’d never make good wine his way and telling him the French methods, just to be contrary. And he said, ‘OK, you think you can do better – you take over the cellar.’ And because I was always looking for conflict, I accepted the provocation. My father set up a bit of theatre – made me take a loan at the bank with really hard terms of repayment but, secretly, he’d already guaranteed it.

When you first started making Franciacorta, it had DOC classification; what happened to give it the more stringent classification of DOCG?

It is very simple. We were not in a historic wine region; it was a newly established one. The DOC covered still wines as well as sparkling, but we wanted to be clear about the appellation. It’s not a sparkling wine from Franciacorta. Under the DOCG, Franciacorta is Franciacorta; just like Champagne is Champagne. We started with a simple premise: we are new; if we want to be better, we have to have rules that are stricter than in Champagne. Back then, we were not obliged to do secondary fermentation in the bottle. But our extra strictness built our reputation.

Was it easy to find consensus about the rules?

The beginning was relatively easy. I mean, not easy – there was discussion. But we found agreement after about a year. And once a few producers like us had raised standards, all the producers were obliged to follow. We built our reputation not only for Ca’ del Bosco but for Franciacorta. It’s a different story today. We introduced the washing of all the grapes, for example, to ensure purity. But the young producers ask, why do we need to improve, we are the best? They are comfortable in their seats on the train and it’s travelling along smoothly. They need to get off their asses and run like we did, 40 years ago!

Ca’ del Bosco Cuvée Prestige Edizione 48 is made with 80.5 per cent chardonnay, 1.5 per cent pinot blanc and 18 per cent pinot noir, from organic vineyards, and was aged for 25 months on the lees. It is widely available for around £40 a bottle. cadelbosco.com