WORDS

Robert Ryan

It was a combination the very thought of which still causes an adrenaline spike in the blood of any racing fan. The high-octane mix of a motorsport-mad Hollywood star, an iconic endurance race, the most successful marque in such contests and the finest competition chronographs in the world. McQueen, Le Mans, Porsche, Heuer. What a starting grid.

All four members of this quality quartet can be seen in the opening minutes of Le Mans, Steve McQueen’s magnificent folly of a film, a box-office failure that, in the 50 years since its release, has grown in stature to become recognised as one of the greatest of race movies. Its perceived faults at the time – mainly a lack of a conventional Tinseltown narrative arc and the fact that nobody speaks any dialogue for the first 37 minutes – seem like positives at this remove, with no corny love story to detract from a visceral depiction of life and sudden death on the race circuits of the 1970s. It is, in fact, more documentary than drama, a fictionalised record of the one season when Porsche 917s battled with the Ferrari 512S for supremacy and a time when health and safety had no place in motorsport.

Le Mans begins with a slate-grey Porsche 911S driving through sleepy French countryside and the eponymous town, before stopping at the racetrack, where the driver, Michael Delaney (McQueen) gets out to inspect a new piece of guardrail. It marks the spot at Maison Blanche where a friend and rival Piero Belgetti died the year before. Delaney leans on the door while his mind flashes back to the fatal impact. As he does so, we get a view of the Heuer watch on his right wrist (although McQueen was not left-handed, as his preferred gun hand in The Magnificent Seven or Bullitt demonstrates), bringing together the four elements mentioned above – star, car, track and timepiece. But how did Heuer come to figure so prominently in the film?

It is mostly down to the supremely talented Jo Siffert, a blisteringly fast and highly successful Swiss racing driver who was sponsored by both Porsche and Heuer. When McQueen needed drivers to coach him on the idiosyncrasies of the Le Mans circuit, the production hired two of the best sportscar drivers available, Englishman and future five-times Le Mans winner and Porsche ambassador Derek Bell, and the already established Siffert, who had won multiple races for Porsche in the company’s 908 and latterly the new beast on the block, the ferocious 12-cylinder 917.

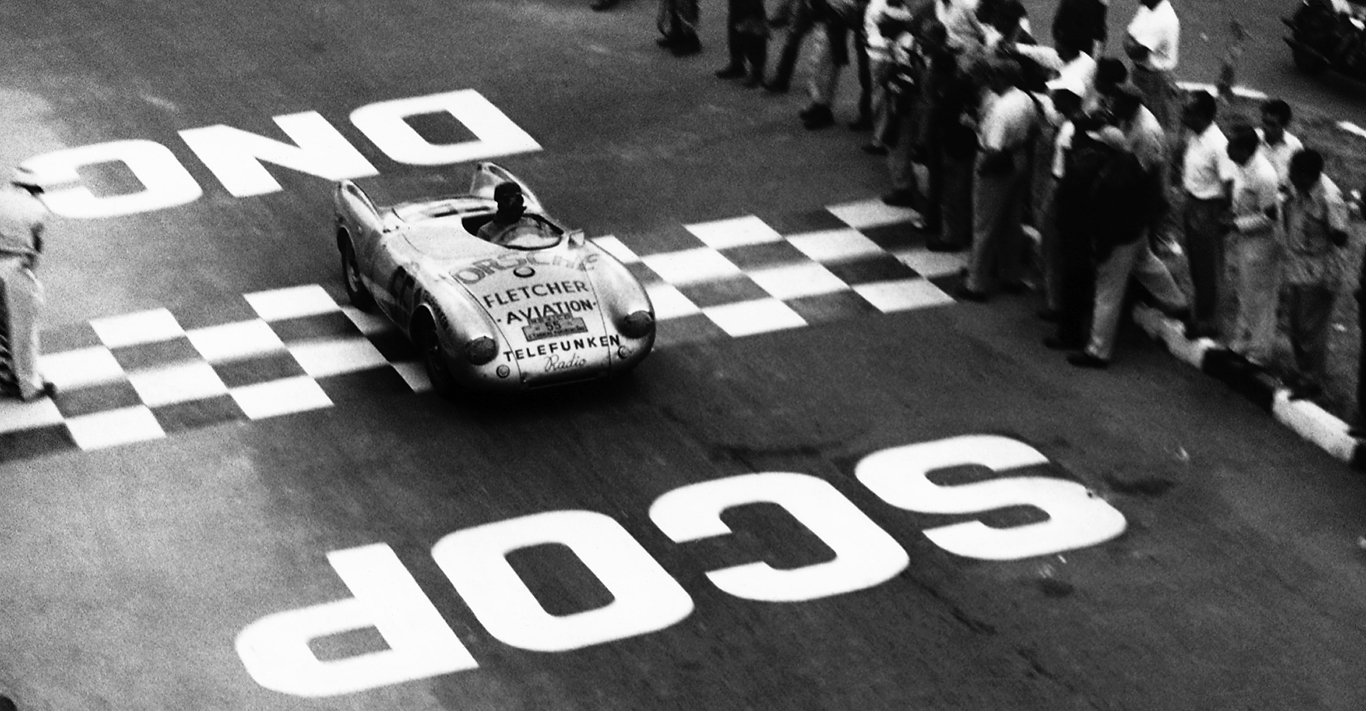

Not that McQueen was a rookie. A committed competitor on two wheels (see the documentary Any Given Sunday), he had come second in the 1970 edition of the 12 Hours of Sebring, co-driving with pro-racer Peter Revson. Oh, and sporting a broken left foot after a motorcycle accident. Their Porsche 908 – which was re-purposed as a camera car for the Le Mans race – was beaten to the flag by Mario Andretti, which was certainly no disgrace, and “McQueen drives Porsche” became a famed ad campaign.

Some years later, Derek Bell described McQueen as a ‘Very, very good’ driver and ‘Much better than we gave him credit for at the time’. He also wrote about McQueen finishing one flat-out stint ashen-faced after being the ham in a sandwich of Bell in the Ferrari 512S and Siffert aggressively bringing up the rear in the Porsche 917, with the actor forced to drive as if his life depended on it. Which it did. As Bell wrote years later, ‘That little escapade proved to me the extent of his skills and bravery’.

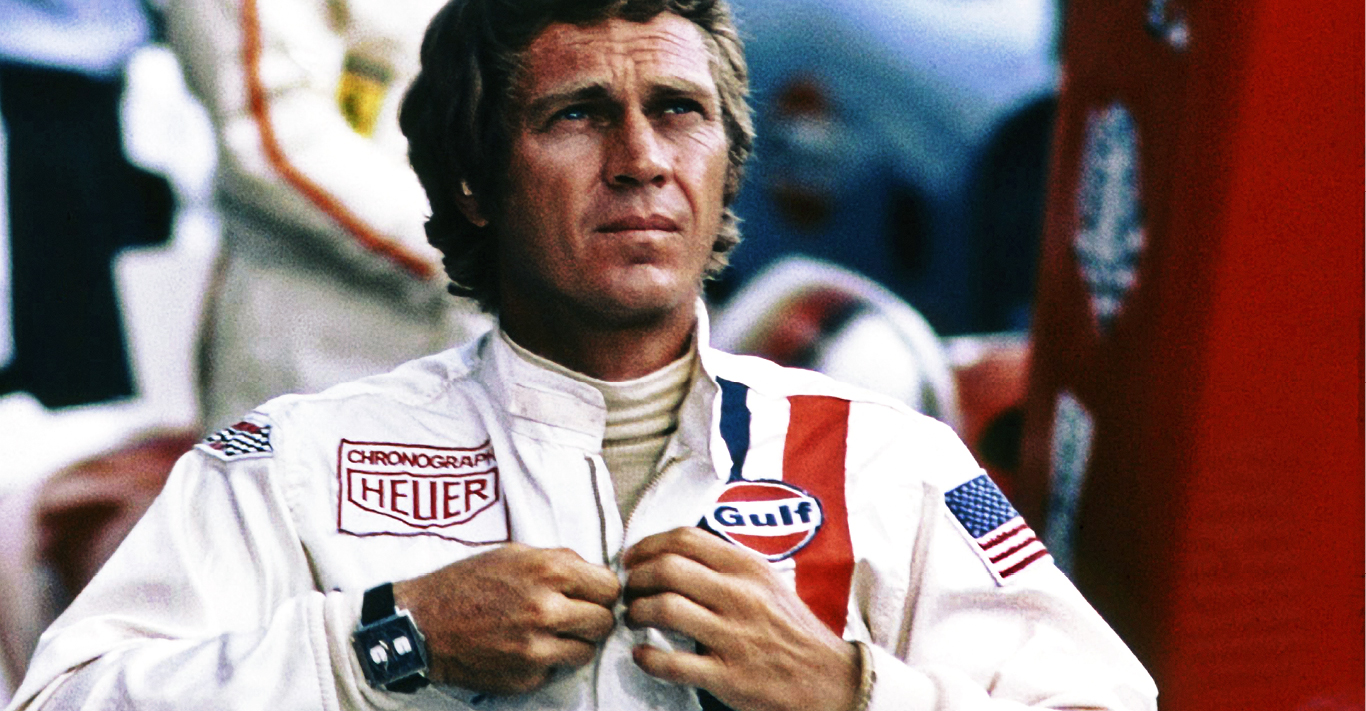

Derek Bell became great pals with McQueen, moving his family into the star’s rented chateau towards the end of the gruelling shoot. McQueen later gave the Englishman a Heuer watch as a sign of their friendship. However, the actor also idolised Jo Siffert. As Jack Heuer, the great-grandson of the company’s founder, describes it in his autobiography, McQueen was asked by a producer how he wanted to look in the film. ‘Apparently McQueen pointed towards Jo Siffert and said he wanted to look exactly like him. Siffert then ran to his caravan to fetch one of his white racing overalls.’ So, throughout the film, Michael Delaney wears the striped Gulf-Porsche liveried overalls with a very prominent Chronograph Heuer patch on his right shoulder, and, of course, the watch itself on his right wrist.

Jack Heuer has said he wasn’t present when the star chose to wear one of his company’s products in the film, although as Siffert always sported one, it is likely McQueen was swayed by that. The wristwatch is actually the square-faced Monaco, but was probably meant to be a Carrera, named, like the Porsche 911 model, for the brutal border-toborder Carrera Panamericana race that took place in Mexico in the early 1950s. Jack does recall being asked for timepieces by prop master Don Nunley and the only stock he had in bulk was the striking but relatively unpopular (at the time; it’s now a classic) Monaco, the Carrera and the Autavia having sold out.

McQueen would later describe the production of the movie as a ‘bloodbath’, plagued by budget overruns, personality clashes and stymied by what he considered unreasonable safety concerns. Originally, he intended to compete in the actual 1970 race, driving with Jackie Stewart, but that tantalising prospect was nixed by the producers and his insurance company. However, they shot hours of actual race film using the 908 and the circuit was then hired for 12 weeks after the real contest had finished. That’s when McQueen got behind the wheel of the 917. The car the star drove in those three months is now owned by Jerry Seinfeld. It isn’t clear how much the comedian paid for it but another example used in the film went for $14m in 2017, twice what the entire movie cost back in 1970. McQueen’s attitude is probably best summed up by Delaney’s most famous line in the film: ‘When you’re racing, it’s life. Anything that happens before or after is just waiting.’

The riveting documentary Steve McQueen: The Man & Le Mans, reveals just how fraught the production was. ‘I’d always wanted to shoot a motor racing picture,’ says the actor in a voiceover. ‘It’s always been something close to my heart. When something is too close to your heart, you have a tendency to become too much of a perfectionist with it.’

In the search for that perfection – which included gluing specific insects to the windshield of the cars – McQueen’s scenes are described as being ‘more dangerous than the actual race’. Derek Bell, who drove the Ferrari 512S in both the competition and the film, almost died when it caught fire, escaping with minor burns. The car was rebuilt and is now owned by Pink Floyd’s Nick Mason. Driver David Piper wasn’t quite so fortunate, crashing his Porsche 917 and breaking a leg. Infection in the wound meant the lower part of the limb had to be amputated. He is thanked in the end credits for ‘his sacrifice’. He did, however, carry on racing after a pep talk from double-amputee Battle of Britain ace Douglas Bader.

That sense of danger, of lives and limbs risked, of men and machines operating at the very edge, comes across in the heart-stopping recreations of the Porsche v Ferrari duel that were filmed at real racing speeds. As one stunt driver says, ‘If you’re meant to be doing 240 miles per hour, then we’re doing 240 in every shot’. They were duplicating a race that McQueen described as a ‘professional blood sport’. Why did they do it, for real and then for the movie? McQueen comments, ‘I don’t think there is any race driver who could really tell you why he races. But I think he could probably show you’.

In Le Mans, along with Porsche, Siffert, Bell and Heuer, he certainly showed us all. We probably won’t see the like again.