WORDS

Gemma Billington

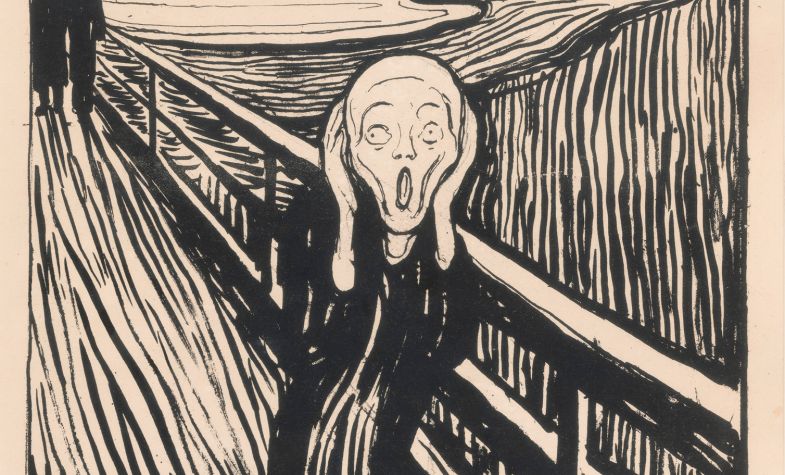

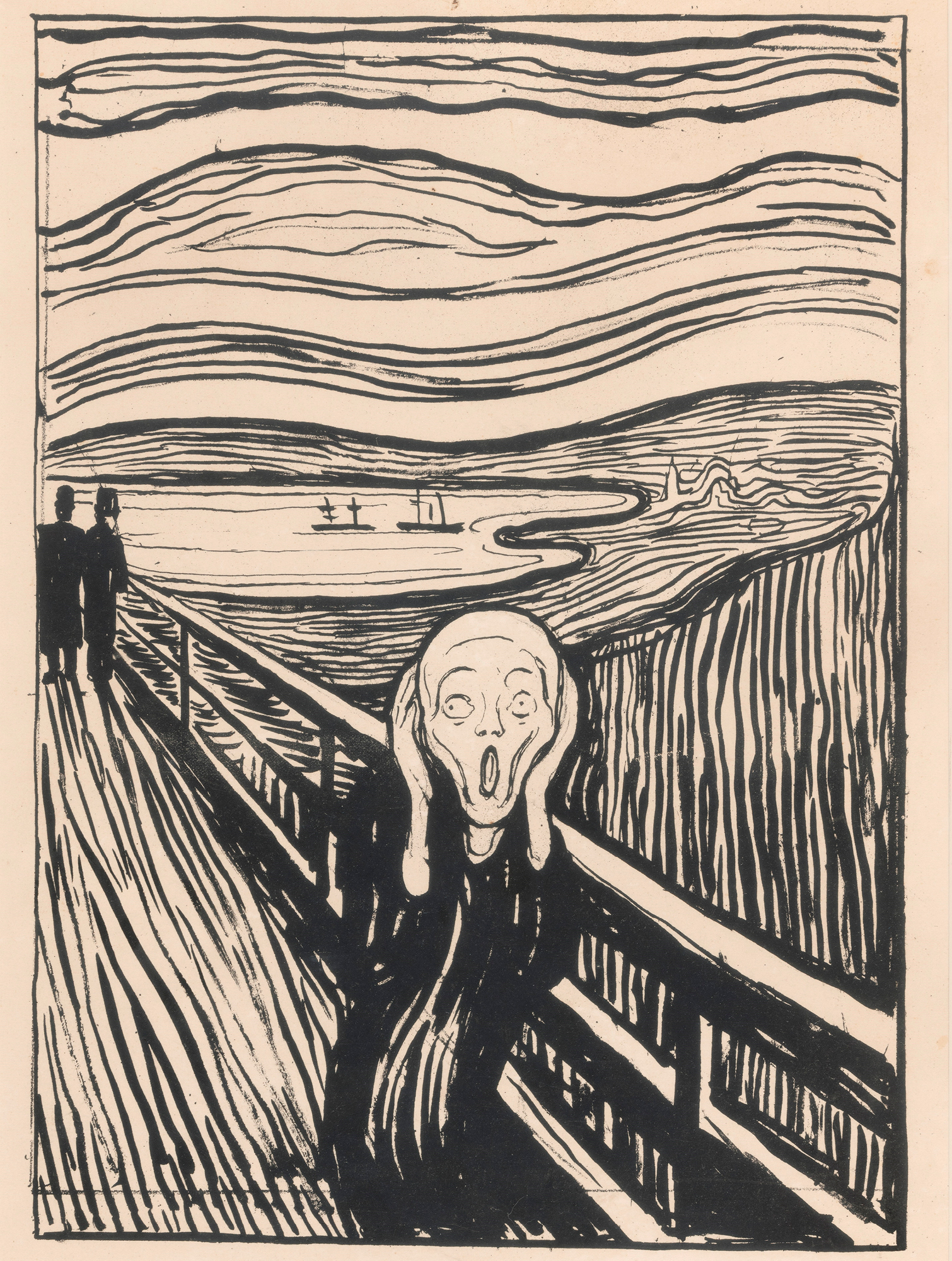

The central figure in Edvard Munch’s existential masterpiece The Scream has no name, no gender or discernible identity. It is startling, verging on grotesque and lacks the beguiling beauty of da Vinci’s Mona Lisa or Vermeer’s Girl With a Pearl Earring. But with the figure’s haunted expression and the painting’s use of jarring, unnatural colour, Munch created one of the most famous and recognisable artworks of all time. The Scream remains an anguished icon of universal anxiety, as recognisable and relevant today as it ever has been.

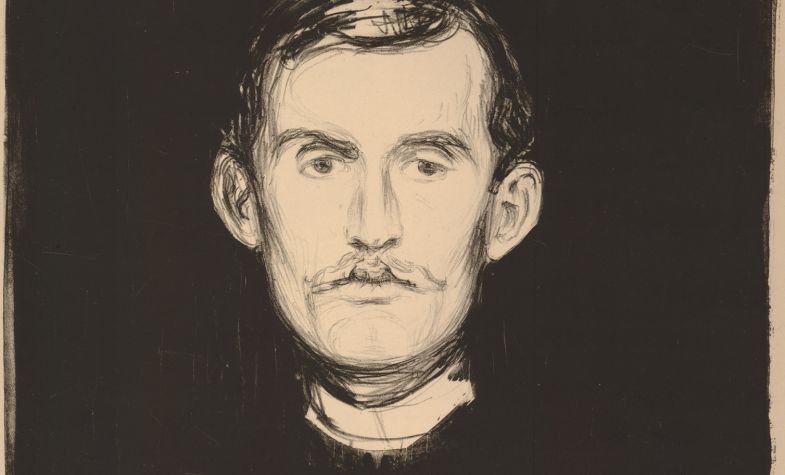

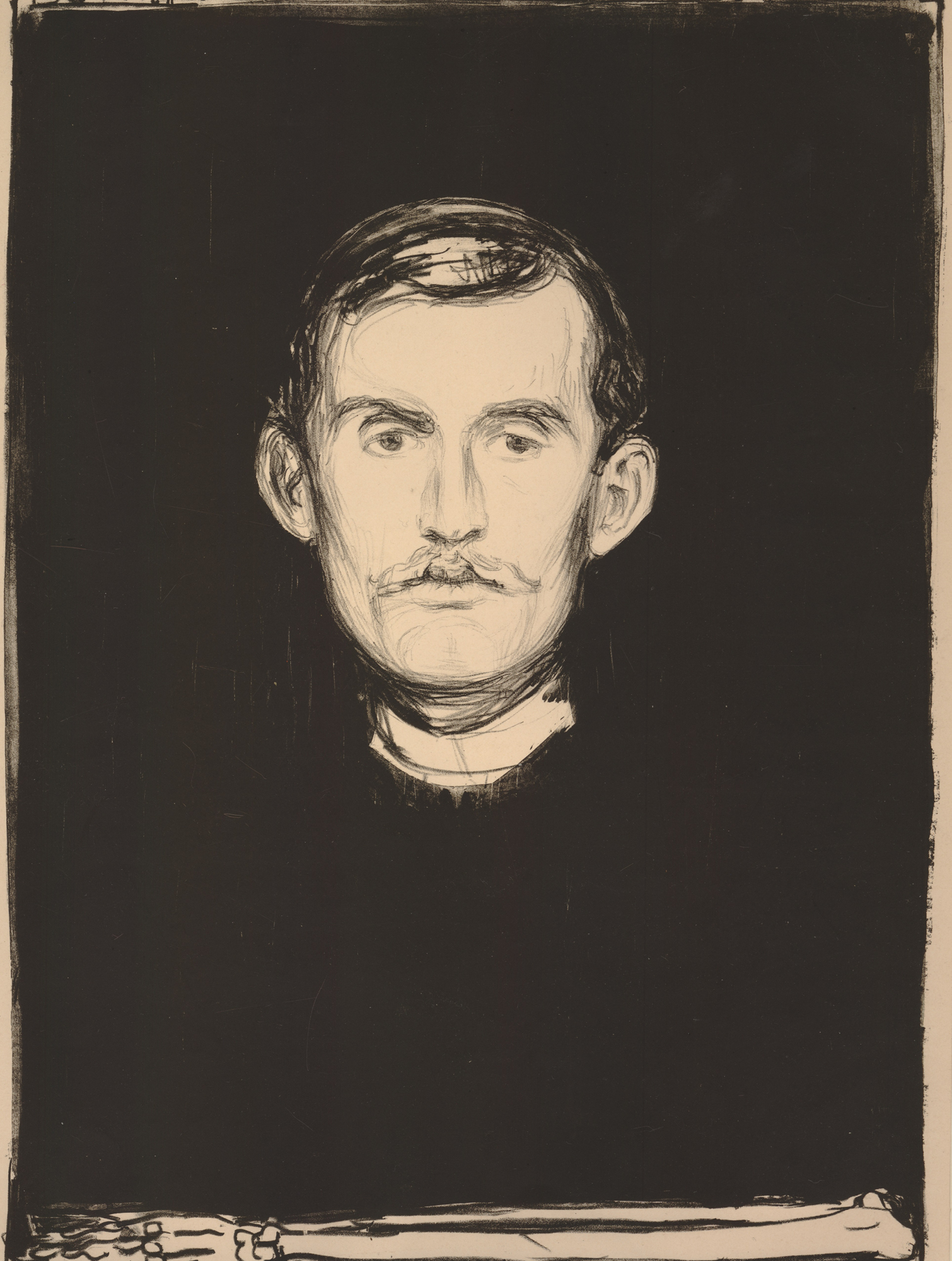

Born near Kristiania (modern day Oslo) in 1863, Munch’s early experiences of death and anxiety shaped his thoroughly modern approach to art. By his teens he had lost both his mother and one sister to tuberculosis. Another sister was committed to an insane asylum for the majority of her adult life. In his vast portfolio of paintings, pastel drawings and prints we see the same morose figures portrayed over and over again. Black shadows loom ominously in the background, the ailing ‘sick child’ – a representation of his beloved sister – looks towards the light of the window, the mourning relatives appear as dark, hunched over figures overwhelmed by grief. Munch’s work is loaded with symbolism and he obsessively depicted the same figures and dreamlike scenarios again and again in alarming colours and abrasive texture.

‘Without anxiety and illness, I am a ship without a rudder,’ Munch once wrote. ‘My art is grounded in reflections over being different from others. My sufferings are part of my self and my art. They are indistinguishable from me, and their destruction would destroy my art. I want to keep those sufferings.’

After studying at the Royal School of Art and Design in Kristiania, Munch travelled to Paris and Berlin, where he found kinship with the bohemian movement and free-thinking radicals of the day such as Friedrich Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud and Henrik Ibsen. Painting-wise, he was inspired by the expressive use of colour developed by his contemporaries Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin. In conservative Norway, Munch’s art was frowned on for its overt depictions of nudity, sexual tension and mental anguish. But the more liberal audiences in France and Germany embraced this bold new style and Munch is today acknowledged as one of the founding fathers of Expressionism.

Although his experiences in Europe helped shape his artistic style, it was in his home country that Munch first painted The Scream in 1893. The painting’s nightmare-esque setting was inspired by an incident two years earlier in which Munch suffered a panic attack (and possible case of synesthesia) while out walking with friends. He wrote of the incident:

‘I was walking along the road with two friends – the sun was setting – suddenly the sky turned blood red – I paused, feeling exhausted, and leaned on the fence – there was blood and tongues of fire above the blue-black fjord and the city – my friends walked on, and I stood there trembling with anxiety – and I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature.’

The central figure in Munch’s masterpiece is contorted in this ‘infinite scream’ – although many critics argue that it is not actually making the noise but is, rather, reacting to nature’s overpowering scream. Just like the ambiguous nature of this figure, the answer lies in the viewer’s interpretation and we are invited to inflict our own emotions and observations onto it.

As with many of his most famous artworks, Munch created multiple versions of The Scream, including two paintings, pastel works and a number of prints. The American art historian Martha Tedeschi described The Scream as being one of a small number of artworks that have ‘successfully made the transition from the elite realm of the museum visitor to the enormous venue of popular culture’. The contorted figure is instantly recognisable and has been parodied and referenced in everything from The Simpsons to Home Alone and the Scream movie franchise. It is also one of only two artworks to have garnered its own emoji – the other being Hokusai’s Great Wave.

More than a century since Munch appalled and intrigued audiences in equal measure – discussions surrounding mental health have never been more prevalent. Ours is the age of anxiety, a term first coined by the poet W.H Auden in his 1947 work of the same name. In this seminal piece of writing, Auden examines the struggle of man to find meaning and identity in an increasingly industrialised world. Today we face a new era of anxiety exacerbated by social media and digital isolation. In this modern age of anxiety, The Scream retains its universal power and appeal.

This month, the British Museum will display a rare black and white lithograph of The Scream as part of a new exhibition on the artist; the most comprehensive in Britain for over four decades. Edvard Munch: Love and Angst explores the mind and methods of the artist with a particular focus on his pioneering prints. While the lithograph will no doubt take centre stage, the exhibition also includes other influential works – some on display in the UK for the first time – including the controversial Madonna and tension-ridden Jealousy and The Lonely Ones. In Munch’s lifetime and for decades afterwards, discussions on mental health were strictly taboo. Today the platform is a lot more open. The digital world both connects and disconnects us and heightens feelings of uncertainty for the future, but in Munch’s haunting masterpiece we are reminded that we are not alone.

‘Edvard Munch: Love and Angst’ will be on display at the British Museum from 11 April – 21 July 2019; britishmuseum.org