WORDS

Ian Belcher

PHOTOGRAPHY

Chris Miller

Haiti doesn’t do mundane. There’s always a frisson of exotic adventure – even on a lazy Sunday visit to a waterfall. I’ve driven less than a mile when, alongside the ruined Peace of Mind Hotel – fractured by 2010’s catastrophic earthquake – my car halts for a swaying funeral cortège: top hats, trumpets, drums, the full New Orleans jazzy send-off.

It’s a mere amuse bouche. To reach Bassin Bleu’s three-tier cascade, I abandon the road outside Jacmel, motor through a shallow river and up a rutted track into a banana plantation. A hike past pineapple plants and tamarind and avocado trees reveals a muscular local with a coil of rope, with which I’m tied to a tree stump and lowered down steep-sided boulders – this is not the National Trust.

I then slip through a narrow fold in the mountain face, entering a circular chamber where vertiginous, creeper-fringed walls swaddle an emerald pool. It’s all very Lost World, but the most remarkable thing? It’s all mine. The dazzling water, the rock ‘diving board’, the limestone polished by a 57m-high torrent; I have it all to myself.

How typical. From Port-Salut’s palm-lined squeaky white sand beaches and Marie-Jeanne’s vast subterranean gallery of abstract sculptures, to countless high-altitude viewpoints, I don’t see another tourist: natural wonders far from the madding crowd. It wasn’t always this way, however. In the decade after World War II, before the grim tyranny of François ‘Papa Doc’ Duvalier, Haiti was a hot, elegant ticket; its casinos and clubs were graced by Noël Coward, Marlon Brando and Truman Capote.

But the past really is another country. The Caribbean’s most mountainous nation now seems indelibly linked to poverty, venal dictators and natural disasters. It’s one of Donald Trump’s celebrated ‘s***holes’. So what? You wouldn’t want his hair; why take his travel advice? Haiti doesn’t offer anodyne luxury, but it guarantees one of the planet’s more intriguing, memorable and exciting breaks.

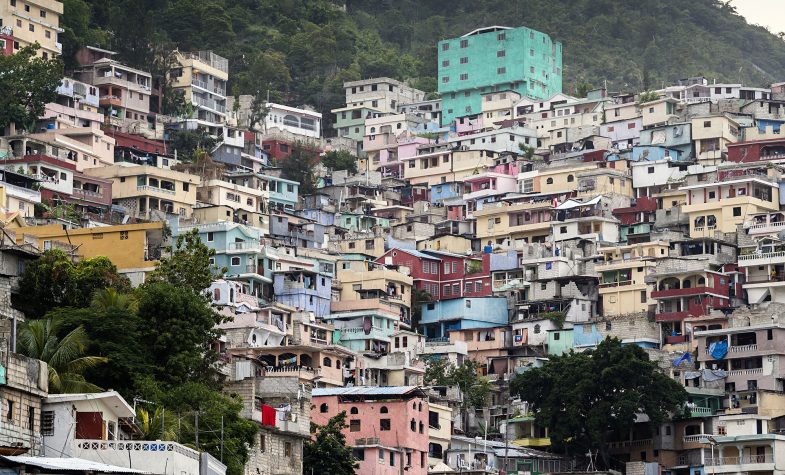

Port-au-Prince sets the tone. The sprawling capital, designed for 300,000 citizens, home to 2.4 million, isn’t for the shy, retiring or claustrophobic. Its frenetic urban theatre sees evangelical churches mingling with beauty parlours, scrap metal dealers and charcoal sellers. Businesses constantly seek divine intervention: from Lord of Power Auto Parts to the Immaculate Conception Lotto Stall and my favourite of all: the Blood of Christ Dry Cleaners (shrouds, presumably, a speciality).

Among the urban tangle that hits peak density among the tombs of Le Grand Cimetière, there are moments of compelling beauty: the exquisite Nègre Marron sculpture of a plantation worker and the Musée du Panthéon National Haïtien’s marble slave girls, their robes so delicate they could be wafer-thin silk.

“Anywhere else, it would boast walkways, coloured spotlights and queueing visitors. Not here”

But in Port-au-Prince, light is often juxtaposed with dark. Nearby in downtown Champ de Mars, I stroll past the gaping void once graced by the white domes and ionic columns of the National Palace; savaged beyond salvation by the quake. You’d never guess this airy sun-washed space was where Papa Doc peered through a personal peephole into the torture room, kept the heads of victims executed during weekly radio broadcasts and rewrote the Lord’s Prayer: ‘Our Doc who art in the National Palace…’

The terrible era after 1957 is immortalised in Graham Greene’s The Comedians. On a soupy tropical night, I make my way to the Oloffson hotel, whose iconic turrets and wrought iron balconies inspired the book’s central location. Tonight hosts local band RAM’s weekly dose of euphoric voodoo ‘rock’n’roots’. Within minutes, Joseph, a towering Haitian émigré revisiting old haunts, slaps a bottle of Barbancourt rum down on my table. ‘Do you drink? Join me.’ Cue a gloriously messy evening.

If music is one strand of the Caribbean country’s DNA, art is another. In the southern city of Jacmel – global epicentre of the 18th-century coffee trade – where the elegantly decaying merchant’s quarter sports al fresco works by Jerry Rosembert (the ‘Haitian Banksy’) I meet Thomas Cantal. In the back of his unlit studio he explains the power of voodoo spirits, lifting a hissing paraffin lantern to illuminate huge papier mâché animal heads and grotesque faces – an unnerving glimpse of Jacmel’s annual masked processions.

Further east, along Haiti’s southern peninsula, there’s more eerie, disturbing darkness. The Marie-Jeanne Cave above Port-à-Piment is a mesmerising four-kilometre-long necklace of 38 underground chambers (a new one unearthed by a recent cyclone), riddled with 60 million-year-old fossils, stalactites and stalagmites.

Anywhere else it would boast walkways, coloured spotlights and queuing visitors. Not here. It’s just me, my guide Victor and his tragically underpowered torch. Names of A-list rock formations including the Dental Clinic, Flat Cul-de-Sac and Man’s Appendage appear to have been christened by an accountant from Hitchin, but I don’t care; I’m just happy to avoid the resident eight-eyed scorpions with 36cm-long antennae: the Papa Docs of the bug world.

If Marie-Jeanne’s cave is deserted, Citadelle Laferrière, Haiti’s only world heritage site, is a guaranteed tourist draw. Quite right too. The western hemisphere’s largest fort, it was built in the far north to defend Haiti – the only nation on earth spawned by a slave revolt – against its former French masters.

It’s spectacular. I hike up 900m-high Bonnet a L’Eveque mountain and enter the monumental structure whose sharp nose suggests an advancing warship. From the top of its three-metre-thick walls, their cement strengthened by sugar molasses and cow’s blood, I gaze across the green peaks to the Atlantic Ocean around Cap-Haïtien. Were it less hazy I could see Cuba, 140 kilometres away.

The view is as breathtaking as the fort’s construction. It took 20,000 former-slaves 15 years to build, killing a quarter of them in the process: a massive labour in vain. The French never returned to fight. Now its 365 redundant cannons and 10,000 unused cannonballs form one of the world’s largest collections of 18th-century armaments.

Back in Port-au-Prince, I sample more contemporary artistry: Le Plaza Hotel’s balconied 1950s courtyard. As I swim, Françoise Hardy’s voice floats through the tropical dusk, bats flit overhead and a huge rat observes impassively from the poolside; a reminder Haiti is many things but never, absolutely never, mundane.

Wild Frontiers offers 10 tailor-made days in Haiti from £3,150pp including accommodation, guided excursions, transfers and flights; wildfrontierstravel.com