WORDS

Ken Kessler

ILLUSTRATIONS

James Graham

A mere three years ago, I was asked to address a roomful of money managers about investing in vintage wristwatches. Here were 30 bright-eyed, eager, young City types, British employees of one of the most celebrated of Swiss financial advisors. Note the ‘Swiss’: at first, it felt like I was trying to tell Eskimos about snow, or Kenyans about coffee, but, no, they were eager to learn.

Aside from a decent watch on nearly every wrist, they were well outside of their comfort zone, their acquired ‘Swissness’ limited to money-making rather than timepieces. Considering that the speaker before me was educating them about the effects of digital technology on future work forces, the subject of ‘Vintage Watches As An Investment Portfolio’ somehow seemed quaint.

But then I reminded myself how mechanical watches had faced off against digital before and won. Sales of new watches were up and vintage watches were on the ascent. That said, my opening remark was: ‘You are 10 years too late’.

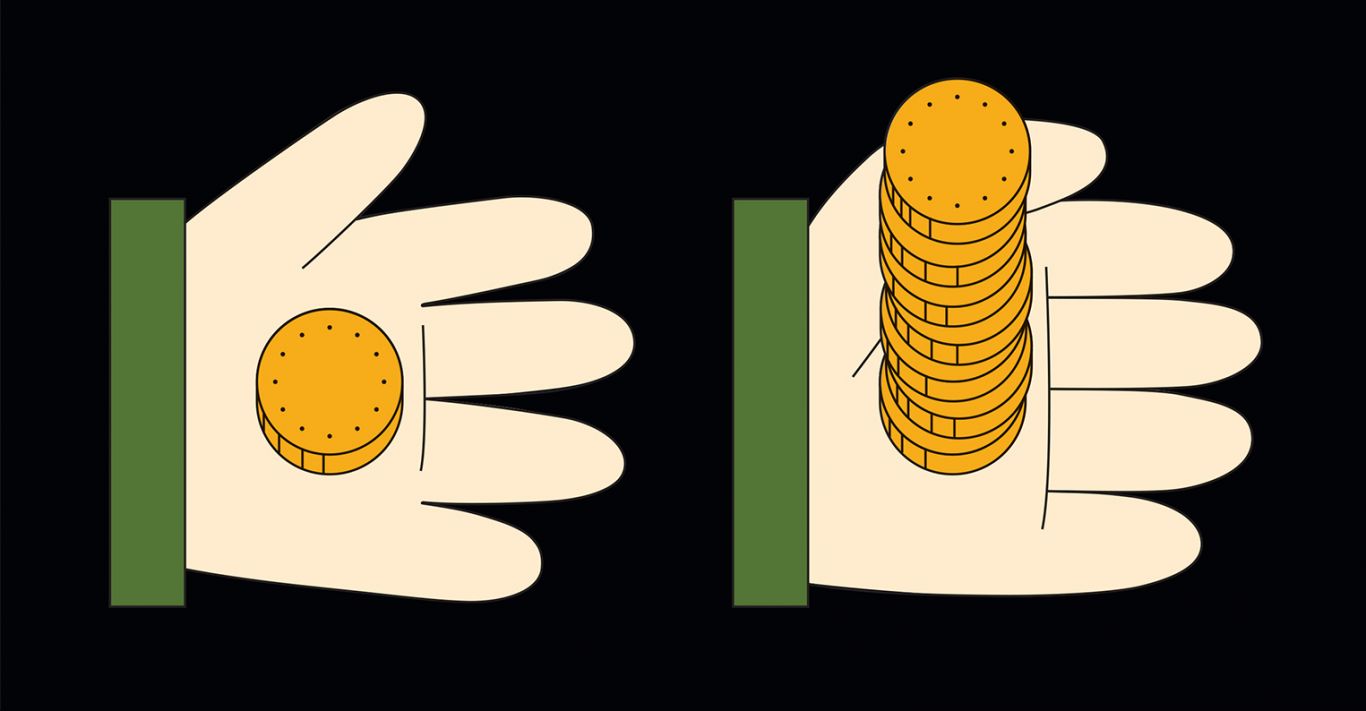

I’ve since learned that it’s never too late to buy into the vintage watch market, because it has yet to plateau, let alone peak. For the newcomer, however, there are now more zeroes on the price tags, so the cost of entry has become prohibitive, especially if buying with the intention to resell. Collecting (and keeping) watches is one thing, flipping them for profit is quite another. When I look at the prices I paid for watches when I started buying and selling, exactly 40 years ago, Rolex Submariners were available for £200 (roughly £1,500 in today’s money). You’d be lucky to find any Submariner today for under £4,000, so the inflation is not about the relative value of the pound: actual demand has created an almost threefold increase in value.

If my 40-year-long vantage point seems too extended a measure over which to chart this inflation, let’s just look at the past decade. As recently as five years ago, most vintage watch dealers would have offered you their first-born to clear their shop of old Tudors – they couldn’t give ’em away. In 2018, you’d be hard pressed to find a “snowflake” Tudor diving watch for under £3,000. Why? Well, the brand was relaunched and rendered universally super-cool. Who knew?

It’s no longer just a case of Rolex and Patek Philippe as the only vintage pieces of interest, although they do still own the upper echelon. No other brands regularly command £1m or more for watches at auctions.

Omega and Heuer are nipping at their heels with all Omegas skyrocketing following the Omegamania auction of 2007, especially the Speedmaster Professional Moonwatch, which increased in value overnight by 30 per cent or more. Heuers that sold for £1,500 three years ago are now fetching £15,000. If you fancy the idea of being a vintage watch dealer, inspired by the ever-increasing competition among buyers, note that there are exponentially more sellers: both online and in physical shops. The established ones have been stockpiling for decades. What’s left are the crumbs – and it helps if you know what to look for.

What to buy now? Leaving aside whispers of collusion among dealers to create demand for specific makes, there are unanticipated but discernible forces that motivate collectors to covet previously unloved or ignored watches. A couple of years ago, an influential blogger decided he adored Universal Genève, currently a dormant brand. Overnight, the watches inflated by 100 per cent or more. (Ben, I still owe you a drink for increasing the worth of my Space-Compax.)

It’s never too late to buy into the vintage watch market, because it has yet to plateau, let alone peak

Military watches worth £200 less than a year ago can command £600-plus. Why? Because British brand Vertex came back from the dead, causing every magazine to write about the Dirty Dozen (watches made for the British military by a dozen suppliers at the end of World War II), so all 12 have shot up in value.

Other brands await rediscovery, but remain bargains if you just want to have a nice, vintage piece on your wrist. My tip? Buy Tissots, Longines, Rados, Eternas and Certinas from the 1950s-1970s. These brands made their own movements, they were – in their day – the match for any of the more celebrated makes, and they can be found for under £200. Hell, I’ve seen mint, automatic Rados for £35. The best bargains of all? 1960s-1980s Seikos, especially the sport models.

Insiders tell me that Heuers (pre-TAG Heuer models, that is) still have a way to go, even though the past few years have seen Autavia chronographs and various models named after motor-racing circuits (Silverstone, Jarama, etc) attaining eye-watering prices at auction. Because the brand has big plans this year for the Carrera, expect the original models to appreciate. And no, my ’64 ain’t for sale.

You never know what will cause an upswing in vintage models, but there is one fact that collectors no longer dispute: every time a watch brand reissues a classic model, the original goes up in price, not down – hence my earlier remark about the Heuer Carrera. And when a major house appoints a controversial CEO with big plans, collectors get excited. Which is why Breitling’s earlier models are soon to shoot up in price, following the arrival of Georges Kern, ex-IWC.

Those City types I spoke to, then, as now, were advised not to buy watches, but to buy shares in online companies selling pre-owned pieces. Kent-based company Watchfinder, founded in 2002, states on its own website that it now has annual turnover in excess of £120m. Selling used watches. Go figure.