Words:

Nick Smith

Photography:

Martin Hartley

‘Lighting a fire in an expedition helicopter packed with barrels of aviation fuel while flying over the Arctic ice isn’t one of the more sensible things you can do,’ says polar photographer Martin Hartley, recalling one of his more surreal brushes with health and safety. ‘It had been stripped bare to make room for extra fuel tanks so we could fly for five hours, so it was like being in the back of a transit van. Outside it was -45°C and when the aircraft’s heating system broke down and the navigational instruments froze, things got a bit challenging.’

By ‘challenging’, Hartley means the aircraft crew and expedition team were freezing too, which meant ‘we’d have to land the helicopter every 20 minutes so we could run around on the ice to warm up.’ Realising this was a huge waste of the fuel they needed to get to their jumping-off point, ‘we did the only thing we could think of, and that was to light a fire inside the helicopter.’ Hartley recalls ‘a five-foot flame from floor to ceiling with all this aviation fuel sloshing around. It was a very bad idea. We were in a flying bomb.’

Despite the obvious danger involved in such an exploit, Hartley says near-death experiences are surprisingly few and far between in his life as a polar photographer. He’s never published his expedition diaries because ‘when you do these things properly there’s not often much to say.’ It’s a job where, despite the occasional pub-style anecdotes, the first priority is to achieve objectives and to live to fight another day. And he’s very good at it, which is why Hartley’s photographic work has been in constant demand for a quarter of a century.

There have been a few incidents of frostbite, snow-blindness and starvation. But apart from that, he’s still in good shape, while the statistics tell their own story. As a photographic ‘embed’, he’s been ‘up north more than 20 times’ and has clocked up a year of his life on the Arctic ice. He’s set foot at 90 degrees north on four separate occasions, photographed Antarctica four times and has trekked to 90 degrees south. All this puts him in an elite band of modern adventurers who explore for a living, rather than ratchet up a tick-box trek to somewhere dangerous. While Hartley’s core work is documenting serious scientific missions and environmental surveys, he’s also done ‘funky stuff’. A job for Hello! magazine took him to Mont Blanc with Princess Beatrice and Richard Branson. The 40-something Lancastrian describes such elevated company as ‘completely normal people. It was a treat to climb in the Alps with these guys.’

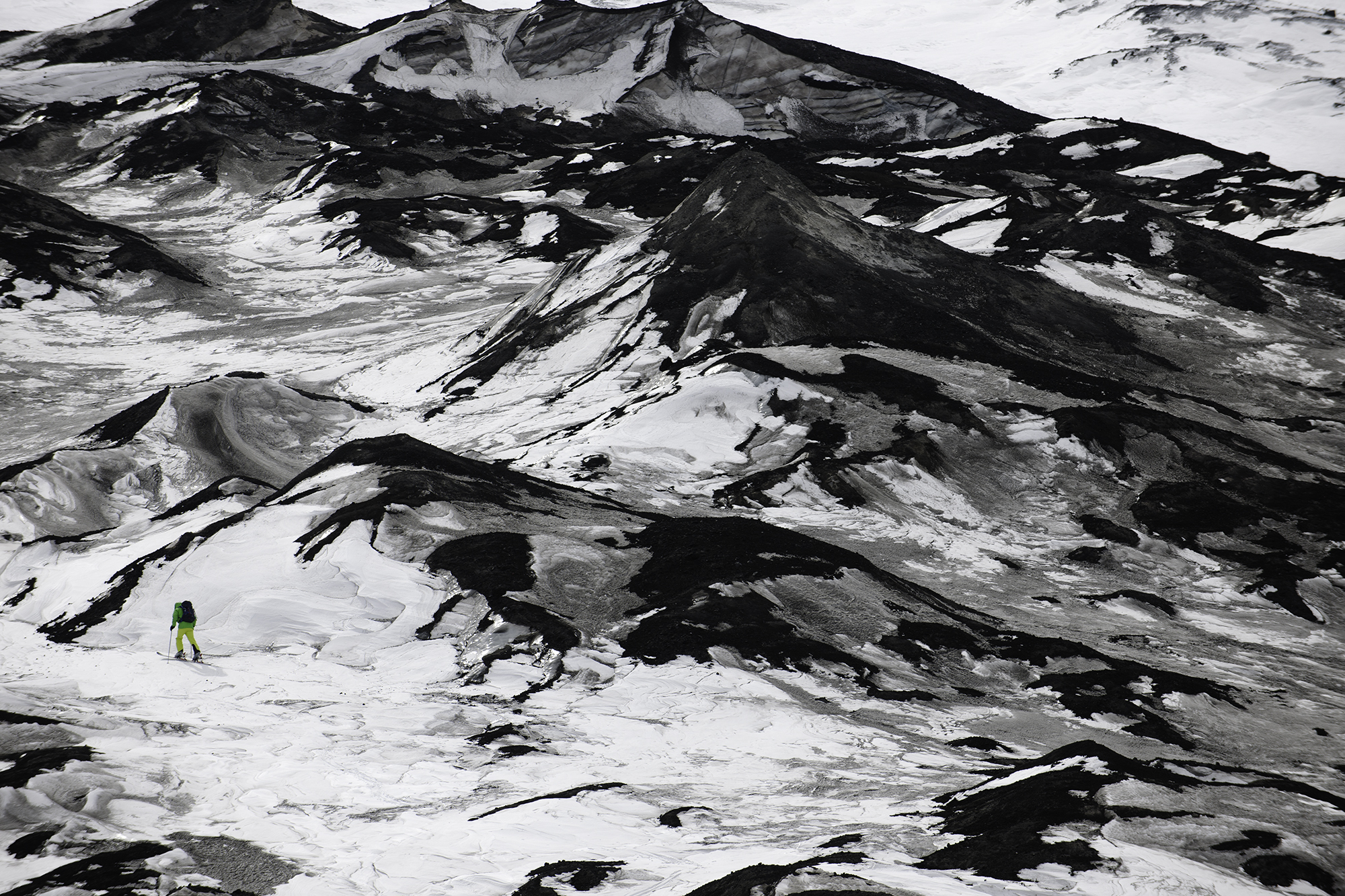

Equally comfortable at either end of the earth, when pushed Hartley admits he prefers the Arctic. ‘It’s my favourite place on the planet. It’s a frozen ocean, dynamic and unpredictable. In Antarctica, it can sometimes feel as though you’re skiing across a frozen car park in Croydon.’ Although he’s reluctant to admit it, Hartley thinks being the photographer is one of the hardest jobs on any expedition, largely due to the fact that ‘I’m carrying more equipment than anyone else. Also, you tend to spend your evening uploading images via satellite while everyone is sleeping. To get the shots you want, you have to run around like a Yorkshire terrier. You cover more ground, get to the tent last, and if there’s any food left, it’s usually cold.’

The Arctic is my favourite place on the planet. It’s a frozen ocean, dynamic and unpredictable. In Antarctica, it can sometimes feel as though you’re skiing across a frozen car park in Croydon

Being a photographer in hostile environments requires a portfolio of survival skills. Hartley says they all came together when he was given an outdoor adventure kit for Christmas as a child. ‘It had everything you needed: a plastic black-and-white film camera, penknife, compass and water bottle.’ With his kit, five-year-old Hartley explored the field behind his parents’ house. It’s ironic, he says, ‘that I started off by pretending to be an explorer and I still am.’ The reason he’s uncomfortable tagging himself with the ‘E’-word is that ‘I have an old-fashioned Victorian view of what an explorer is. It’s the guy who goes to unknown places and comes home with scientific information. It’s got nothing to do with doing dangerous stunts.’ Today there simply are no longer the challenges Shackleton and Scott were faced with, ‘when there really were blanks on the map. Back then, when explorers walked out their front door, they didn’t expect to return for years, if at all.’ It’s also safer now: if Scott had today’s digital comms ‘he would have probably survived. He could have contacted expedition base with his GPS co-ordinates, in the belief that he had a reasonable chance of people coming out to find him.’

One thing that has never left Hartley is the sense of challenge. Even with a couple of dozen hardcore polar trips under his belt, he still feels the pressure. ‘The night before you start, you’re praying for a bad weather report so you can have one more night in a warm bed and another evening in the bar with your mates.’ But the call rarely comes and ‘you’re soon in the helicopter flying to the drop-off point,’ where everything has to be unloaded in minutes because the pilot won’t switch off the engines ‘just in case they don’t start again. Then you watch it leave until it’s a distant speck in the air and you really are alone. Then you get started.’ The first ten days are a revelation: ‘sure, you’re a bit chilly. But then, especially if it’s a long trip, you really get stuck in. By the end, you’re praying the pick-up plane will be delayed so you can have one more day on the ice.’

On returning home, Hartley says he sometimes finds reintegrating into his regular life ‘a bit trivial. You get used to it eventually, sort of. But you’re always wanting to get back out on the ice.’

To see more of Hartley’s work, visit martinhartley.com